I’ve been writing on the internet for over ten years. Most of that writing is gone — it was on old blogs that don’t exist anymore (thank goodness) or is buried deep in the archives of publications that turn out multiple articles per day. But for most of the time I’ve been writing, I didn’t have any strategy in mind. In the early days, I’d make a simple Squarespace blog and write whatever came to mind. The process for bigger publications was similar: I’d have a thought that I wanted an audience to know about, submit a pitch, hope it’d be accepted, and write the piece.

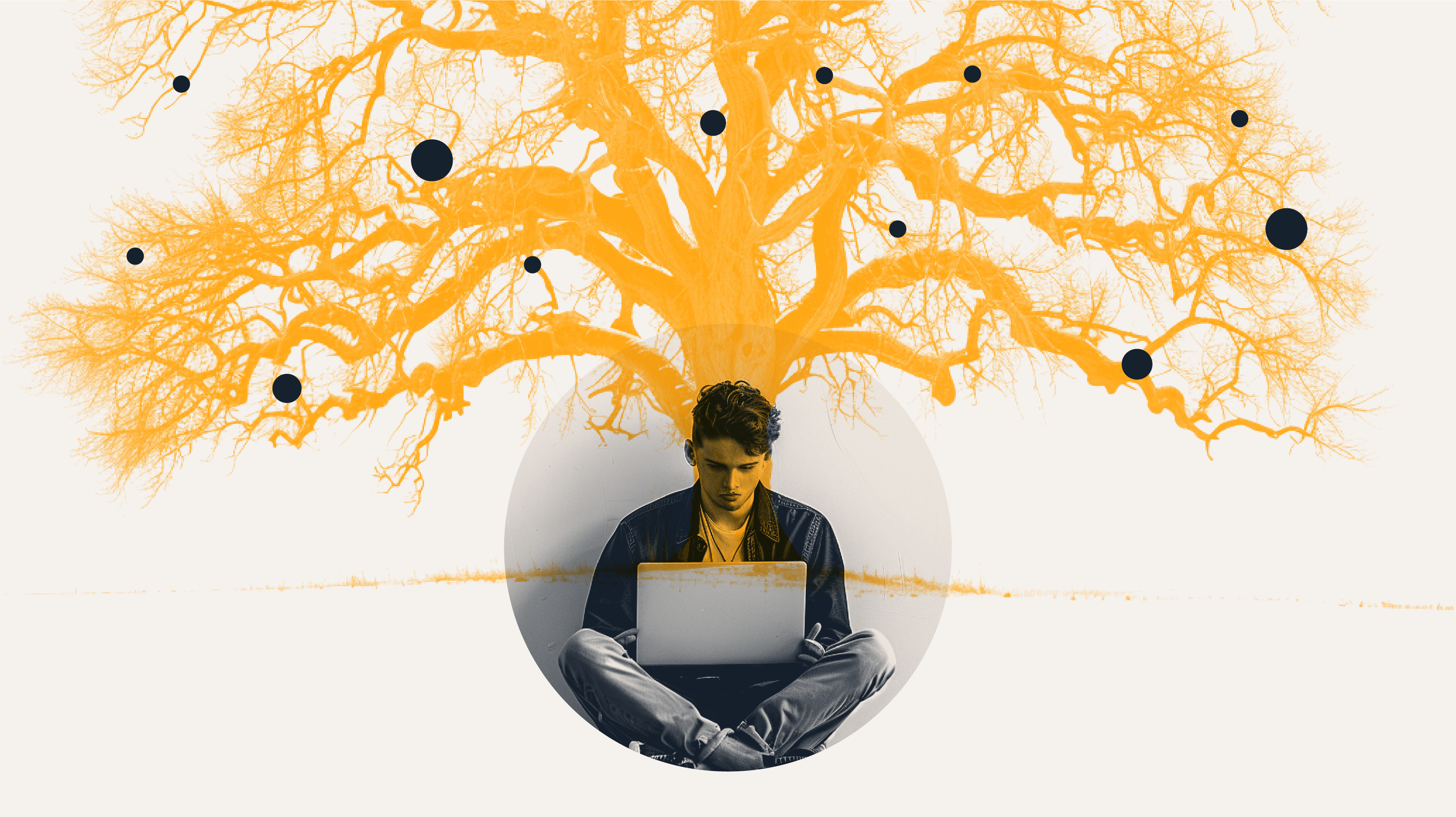

There’s nothing wrong with this approach, but it falls short in its ability to serve a single, helpful idea and share it with the world. If you want an idea to grow beyond yourself, it takes a good deal of nurturing. A single article might find an audience, but the idea is just a seed—and it won’t grow into a mature tree on its own without being watered. I’ve never sat down to make a plan for how to do this, but over time, I discovered one. It was only in hindsight that I realized what I stumbled into and how it worked. If you are a writer, or want to be one, and you have an idea that you want to nurture, here is what I recommend you do:

Picture your idea as a seed that needs to grow. Your words are the water and different forms of writing are the different stages in the plant's growth. Your goal is to take that idea from a seed to a full-grown tree. What are the stages of growth, and how do you nurture the idea to help it mature? There’s no one way to do this, but let me give you some ideas to start with.

The Seeds

The smallest unit of writing on the internet is the tweet. Tweets are where the seeds of ideas are planted. There are many frustrating things about Twitter, but one thing it is great for is working out the seeds of ideas in public. Being able to have a thought, test it out, see if it lands or doesn’t land, get helpful feedback (if the people who follow you are helpful, of course), and bring the idea into conversation with others is helpful to see which seeds should be watered and which should be left by the wayside.

The next level of this is simple tweet threads. Expand the ideas from singular tweets into more coherent, fleshed-out thoughts to get an idea of what it would be like to work the idea out in a longer form somewhere else and continue to gather feedback to help you refine it.

The Roots

After the seed has been watered, it can start to grow roots. The roots of an idea are a personal newsletter where the idea is further explored in small ways from many different angles. A newsletter is the idea's roots for a couple of reasons. For starters, just as roots split off in every direction and some roots are big and some are small, a newsletter lets you go in any direction you like while still centering around the main idea. You can publish as much as you want, whenever you want, and go down any rabbit trail you think is helpful. This allows people who are interested in the topic to go down the rabbit trails with you and explore every nook and cranny of the idea.

A personal newsletter is also the root because it holds you in place. You’re not beholden to the winds of algorithms or editors. Instead of renting your space on the internet, you own it. When the 24/7 social media conversation moves on from your idea, you can continue working on it with people who care about it and have opted in to your writing. A personal newsletter creates stability that can allow the idea to grow over time.

The Trunk

From the watered seed of the idea and the sturdy root system that has developed, the tree trunk can start to grow. The trunk is the first part of the tree that is visible to people who are just passing by and weren’t looking for you in the first place. The trunk is long-form articles published at more established publications.

Larger publications help get your idea in front of audiences who have never heard of you before and trust the publication more than the individual writers who write for them. Their audience is several orders of magnitude larger than yours, and writing for them gives you both exposure and credibility. When published in a larger publication, the chances of your article getting passed around from person to person are far greater than for anything you write for your newsletter. But because you have done the work of planting seeds on a site like Twitter and building a root system with your newsletter, when people discover you through your article, they have a place to find more of your writing and stick with you over the long haul.

Once you have established your root system, it’s a good practice to set a personal goal of pitching a certain number of articles to different publications on a schedule. Maybe that’s one article per month or per quarter. But these articles should be some of your more thoughtful and fleshed-out material, since they’re intended for the largest audience and will be for an established publication. Sometimes, you will just make a cold pitch through the publication’s website. But Twitter is also a great way to build relationships with editors.

These three steps—tweets, newsletters, and published articles—create a feedback loop that helps your idea grow through writing on the internet. Doing this will go a long way to growing your ideas. After this, the only thing left to do is to leave the internet.

The Canopy

After the trunk has grown, finally, you have the canopy of the tree. The leaves and branches. This is what people see, the fullest expression of the idea. In publishing, this would be a book. This is the hardest part because it’s the part that is most out of your hands, and it’s also the most work. There are lots of things that go into publishing a book, but hopefully, after writing in the other three buckets for a while, you have picked up some themes, figured out what has resonated most, and are able to start organizing the ideas into a book-length outline.

I’ve only written one book (and it’s still in the editing phase), but here is how I thought through outlining it. I had one big idea that was the backbone of the whole book. That one big idea contained about 13 other smaller ideas that explain the big idea. Those 13 ideas were the chapters of the book. And those 13 ideas were made up of about five to eight even smaller ideas, which formed the sections of each chapter.

Once you have your outline, reach out to some of the editors you’ve worked with or another published author you’ve developed a relationship with and ask for advice on how to start a conversation with a publisher. Every situation is different, so it can be much more complicated than this. But at this point, you have already made it much further than most people with an idea that they never do anything with.

Not everyone has to write a book. This doesn’t have to be your end goal. But a book allows an idea to find its fullest expression and bring a wider audience to the other writing you’re doing in your newsletter and other publications. That said, if all you do are the first three steps, you’re doing great.

The Fruit

Finally, there is the fruit that the tree of the idea bears. At the end of the day, it’s not about audiences or books or even the love of writing; it’s about helping others. That’s the reason for going through this whole process in the first place. You believe that your idea can actually help people. That means you have something to steward, nurture, and grow. It’s not about your platform; it’s about stewarding an idea to help others who would benefit from it. There’s nothing like hearing stories from readers about how the idea has helped them.

While I didn’t set out to apply this strategy to my writing in the past, this is the advice I wish someone had given me when I first set out to write on the internet. If you’re just starting out, don’t try to go from zero to a hundred. Take your time. Plant a tree. Start with a seed and nurture that seed until it grows. One day, you’ll see it bear fruit.

Ian Harber is the Director of Communications and Marketing for Mere Orthodoxy. He is the author of the book, Walking Through Deconstruction: How To Be A Companion In A Crisis Of Faith (IVP '25). He has written for The Gospel Coalition, Mere Orthodoxy, RELEVANT, and more. Ian lives in Denton, TX with his wife and two sons.

Topics: