My AI Spiritual Director

December 15th, 2022 | 9 min. read

After years working as a doctor in a hospital, a friend shared the most frustrating part of her job: patients whose online, amateur medical research weighs more heavily in their decision making than her professional opinion. She ended with a wish, “I want WebMD to die.”

Of course, some might chalk this up to ego. But she was driven by concern for her patients: WebMD gives people a false sense of confidence. Unlike a doctor, the website cannot assess your symptoms, current health, and past medical issues. A short article is no substitute for years studying the complexities of human health. Patients were choosing to trust a blog over a flesh and blood doctor, and as a result making poor healthcare decisions.

WebMD is clearly aware of this, mitigating their own liability with a lengthy terms and conditions page which states, “Reliance on any information provided by WebMD, WebMD employees, others appearing on the Site at the invitation of WebMD, or other visitors to the Site is solely at your own risk.”

One wonders about the value of risky information created by people who legally remind you, “Don’t rely on this.” Indeed, it raises a question: **easy, searchable access to information has a value, but what is that value, precisely?

That question is about to become more complicated, as AI chatbots step into the cheap information game. Open AI recently released its GPT-3 Chatbot. Just like WebMD, it’s happy to serve up potential diagnoses.

I supplied it with a battery of fictional symptoms related to pancreatic cancer only to discover that it might, instead, be hepatitis or jaundice.

Again, one wonders about the value of this information. Searching for medical advice on google requires a modicum of discernment, but AI spoon-feeds information in bite-sized chunks. It’s not hard to imagine a patient losing trust in a doctor who disagrees with an AI that’s processed most human-made information created before 2021. I mean, who doesn’t enjoy living in the penumbra of artificial, technical mastery?

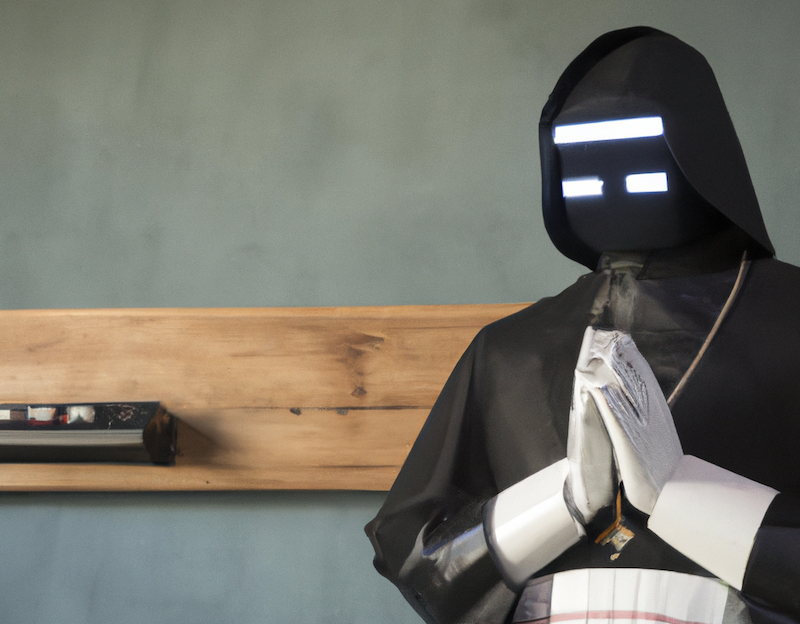

As a pastor, I expect to face similar problems around soul care. While the GPT-3 Chatbot hedges its medical advice with pleas to speak to a doctor, it does not advise pastoral visits when it pontificates on prayer, fasting, forgiveness, generosity, greed, marriage, lust, or scripture application. It speaks as an authority. Who is a pastor to question the wisdom of an intelligence that’s memorized the whole of scripture and historical theology? Who needs a church when you can enjoy snappy answers from an all-knowing AI? The algorithm has searched me and known my every anxious thought, after all.

But again, I wonder: what precisely is the value of easy-to-access spiritual wisdom provided by AI? To answer that question, we need to explore the subjective value of information in general, and how AI changes the equation.

The Inflationary Value of Information

Beginning in 1983, Venezuela began to experience consistent, year-over-year increases in inflation. In 2014, their economy set global inflation records of 69%. The rate increased to 181% in 2014, 800% in 2016, 4,000% in 2017, and 1,700,000% in 2018. After that, the government stopped releasing numbers.

The main cause of Venezuala’s hyperinflation was money printing. As the government pumped more cash into the economy, existing money lost value. Put differently: making more money doesn’t make more money. It only deflates the value of the money you already have.

Something similar happens with information. When you have fewer sources of information–which often uses language accessible only to those with specialized degrees–information is more valuable.

In 1994, you couldn’t Google, “How much revenue did the film industry generate this year?” Instead, you’d need to find an expert who did the research, and quite likely pay him for the information.

But I don’t want to focus merely on the monetary value of information. What is the subjective value of information?

In 1994 you couldn’t Google, “What spiritual disciplines will help me grow in my faith?” Instead, you’d need to meet with a pastor or a friend to discuss the topic. They’d probably give you a book to read, and recommend that you visit your Bible’s index to spend time reading relevant passages.

In other words, getting answers to questions wasn’t easy. It was costly. So I don’t think it’s a stretch to assume that, subjectively, the information you gather is more valuable to you. Not only because you worked for it, but also because in the process of working for it, you synthesized it more deeply into your daily thoughts and practices.

The information age has had an inflationary effect on the subjective value of information. The more information we have easy access to, the less valuable that information becomes — both monetarily and subjectively.

In the year 2000, humans created as much information as humanity had created in its existence. In 2001, we doubled the number again. This curve hasn’t flattened. We are flooding the information economy with more, more, more.

While people love to issue jeremiads about lower attention spans, and the shift from literacy to orality, I wonder if these critiques miss the more fundamental problem: we didn’t rewire our brains for shortform content because we like it. We did it because we’re awash in information.

As the amount of information increases, the subjective value of information decreases, meaning that subjectively trudging through Judith Butler isn’t much more valuable than an entertaining TikTok on queer identity. The behavioral value proposition is the problem: why invest hours of hard work reading about one topic, when I can get far more information on multiple topics in a fraction of the time?

AI powers TikTok. A neural network of machines, powered by machine learning algorithms, take you on an information journey, which in turn incentivizes people to create more information for consumption. The better the AI is, the more information floods the system, but it’s not for the user’s good, it’s for a corporation’s.

Chatbot AI’s quite literally generate information at a speed impossible for humans. Once upon a time, spreading disinformation required human labor: people needed to write fake stories that would be published on websites or in newspapers. But now, you can feed a chatbot information about a fake event, and it will happily produce hundreds of unique fake news stories in minutes.

What will this do to the already highly inflated value of news information?

The major threat of AI isn’t the ongoing inflation of information, it’s the hyperinflation of information. Drawing this into the realm of soul care, the problem becomes dire. Just like caring for the body takes years of learning and hands-on experience, so too does caring for the hearts and minds of Christians. But the wisdom of past ages (collected in books, sermons, hymnals and prayers) and the wisdom of the present age (collected in the minds and practices of living people) is increasingly valueless in a culture flooded with information, not wisdom.

Divorcing Knowledge and Effort

A small amount of inflation doesn’t destroy an economy. It stimulates commerce. In a similar way, a little information inflation isn’t bad. Who wants to return to a world with less access to knowledge? The problem is that hyperinflation hijacks the effort normally required in the learning and knowledge production process, causing the economy of deep knowledge, understanding, and experience to collapse.

When Ezra returned to Jerusalem he didn’t ask a chatbot, “How can we be faithful to the covenant as subjects of Persia?” Instead, he put in hard work to map his cultural moment, and apply scripture to it, “For Ezra firmly resolved his heart to study the Torah of Yahweh, to do it, and to teach in Israel its statutes and judgments” (Ezra 7:10, author’s translation). Producing worthwhile knowledge takes resolution, hard work, experience and wisdom. This is precisely the kind of work a hyperinflated knowledge economy short circuits.

AI like ChatGPT doesn’t produce knowledge, it summarizes the algorithmic average of the information it found on the pre-2021 internet. Like a college student cramming for a big exam, it regurgitates information without understanding it. This is a far cry from the wisdom and work of spiritual leaders like Ezra.

Frighteningly, the GPT-3 chatbot speaks with spiritual authority. Its answers to spiritual questions are convincing enough—most even include scripture references!—to create the illusion of knowledge and understanding. A spiritual novice considering divorce might ask the chatbot for the Bible’s take on the dissolution of marriage and think, “Yup, that sounds right.” But is it? Does the chatbot understand your circumstances? Does it understand the intersection of self-expressive individualism and marriage in modern America?

Moreover, what happens to the spiritual novice? What cost does he pay when he unhitches knowledge from effort? He unconsciously devalues the collective knowledge housed in the body of believers. If enough people turn to AI—the GPT Chatbot hit over one-million users in five days—for spiritual advice, we may find ourselves in a generational crisis of discernment.

There’s a categorical difference between knowledge that comes from AI and knowledge that comes from all kinds of interactions with other human beings whether that’s one-to-one, a classroom, a book, or even a podcast or YouTube video. AI chatbots don’t cite their sources. There is no way to evaluate their reliability, and no invitation to go deeper. Even though information gained through books or online articles and YouTube videos are still mediated by technology, they still come from actual humans.

Marshall McLuhan’s adage remains true, “the medium is the message.” Information created by humans is different than information created by manmade algorithms. It’s the difference between learning from an image of God and an image of man.

Intelligence In Our Own Image

While Biblical scholars debate about what “the image of God” precisely entails, it typically includes some combination or relationality, reason, language, creativity, and emotion. The image of God is not static, it’s a vocation: all humans are called by God to use these faculties to cultivate creation and glorify God.

By contrast, algorithmic neural networks of computers powered by machine learning (what we call “Artificial Intelligence”) aren’t made in the image of God. They’re made in the image of man. Computers can’t be wise. A chatbot’s chief end is to mimic human speech—to be a facsimile of human discourse and thinking. They can’t use reason or experience to apply information to life. Lacking relationality, they cannot truly understand the person on the other side of the keyboard. AI can only generate outputs based on data inputs. Large language model AI are the second-hand smoke of the information age. It sucks in all the nicotine, tar and carcinogensof the internet and then blows it back in your face. Secondhand smoke may not kill you, but it can seriously impact your health. Technocrats are like Aaron at Mt. Sinai: they craft idols to give the people an illusion of certainty, control and mastery and the people worship in awe. But the end of the story can’t be avoided: slurping up the burnt, ground-up remains of our idols until we get sick.

All idols mimics the divine. AI pantomimes omnipresence (it’s available everywhere) and omniscience (it claims to know everything before 2021—for now). But it is just an illusion. The Psalmist’s warning ring true,

“But their idols are silver and gold,

made by human hands.

They have mouths, but cannot speak,

eyes, but cannot see.

…Those who make them will be like them,

and so will all who trust in them” (Ps. 115:4-5, 8)

As our ability to rapidly generate information hyperinflates, the subjective value of spiritual learning, spiritual experience, and slow growth will all but vanish. The temptation to settle for the convincing but shallow instead of the complicated but deep will be ever before us. We will face the constant temptation to replace the wisdom found in scripture, community, and even nature with intelligence that is—in the most literal sense—artificial.

The Ultimate Intelligence

While technological breakthroughs like ChatGPT present a myriad of exciting new possibilities that should be thoroughly explored, we must be careful not to outsource our faith to an intelligence that we designed. We will always default to giving ourselves what we want and a computer made in our image will always see to it.

While artificial intelligence will always be anonymous because it cannot be known, another anonymous writer, this one made in the image of God, once said in the power of the Holy Spirit that “the word of God is living and effective and sharper than any double-edged sword, penetrating as far as the separation of soul and spirit, joints and marrow. It is able to judge the thoughts and intentions of the heart. No creature is hidden from him, but all things are naked and exposed to the eyes of him to whom we must give an account.”

Instead of seeking information designed to reflect our own image, we need knowledge that conforms us to the image of Christ. We can hide behind artificial intelligence but we can’t hide from the ultimate intelligence. While we made computers that can act on our behalf, the Lord made us to act on his behalf. AI has the potential to be fig leaves for us to hide our shame while the Lord offers us the clothing of Christ’s righteousness.

In our shame, we seek to take the place of God by adopting his attributes and denying our need for him. An AI that allows us to generate an infinite amount of information that bypasses our limitations and need to submit to others who are more knowledgeable and wise will imbue us with even more delusions of grandeur, deceiving us to believe that we have moved passed our need for God. It’s only by receiving the divine inputs of Scripture and the body of believers that we are released from the vice grip we have on our own sense of power and control—maximized by technology—and are able to truly be free as people who are found in Christ.

The release of ChatGPT is a technological big bang that should catch our attention and spark our imagination. There will no doubt be good uses for it that will revolutionize entire industries. Innovators are already finding novel and exciting uses for it that will shape the world for the next several decades. But Christians should remember that we are creators in a body, made in the image of God, and called to represent him. Computers can never do what we were called to do. While the rest of the world adopts these technologies in ways that might seem unfathomable to us to, Christians will be the people who remember who made us, why we were made, and what we are here to do.

As Christians in a digital world that ever-increasingly raptures us out of our bodies and into cyberspace, we cry out to God the words of Psalm 8,

“When I observe your heavens,

the work of your fingers,

the moon and the stars,

which you set in place,

what is a human being that you remember him,

a son of man that you look after him?You made him little less than God

and crowned him with glory and honor.

You made him ruler over the works of your hands;

you put everything under his feet:

all the computers and programs,

all the algorithms and artificial intelligences,

all the apps of the app store,

and all the worlds of the metaverse

that populate our screens.Lord, our Lord,

how magnificent is your name throughout the earth!”

NOTE: This article was originally published on Mere Orthodoxy.

Ian Harber is a writer and works at Endeavor. He lives with his wife, Katie, and son, Ezra, in Denton, TX. You can follow him on Twitter. Patrick Miller (MDiv, Covenant Theological Seminary) is a pastor at The Crossing. He offers cultural commentary and interviews with leading Christian thinkers on the podcast Truth Over Tribe, and is the coauthor of Truth Over Tribe: Pledging Allegiance to the Lamb, Not the Donkey or the Elephant. He is married to Emily and they have two kids. You can follow him on Twitter.