This post is part of a series exploring Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death chapter by chapter. You need not read the book or previous points to appreciate this one. You can find part 1 here. In this essay, I will explore Chapter 1: The Medium is the Metaphor.

In the opening chapter of Amusing Ourselves to Death, Neil Postman observes, “As I write, the President of the United States is a former Hollywood movie actor.” He wasn’t writing about Donald Trump in 2016.

He was writing in 1985 about Ronald Reagan. Thus begins an epic jeremiad about the then-recent fad of politicians, scientists, and academics sitting for interviews on late-night shows and hosting Saturday Night Live. It’s almost comical to read today because I can hardly imagine a world where this sort of thing doesn’t happen.

“Our politics, religion, news, athletics, education and commerce,” writes Postman, “have been transformed into congenial adjuncts of show business, largely without protest or even much popular notice.”

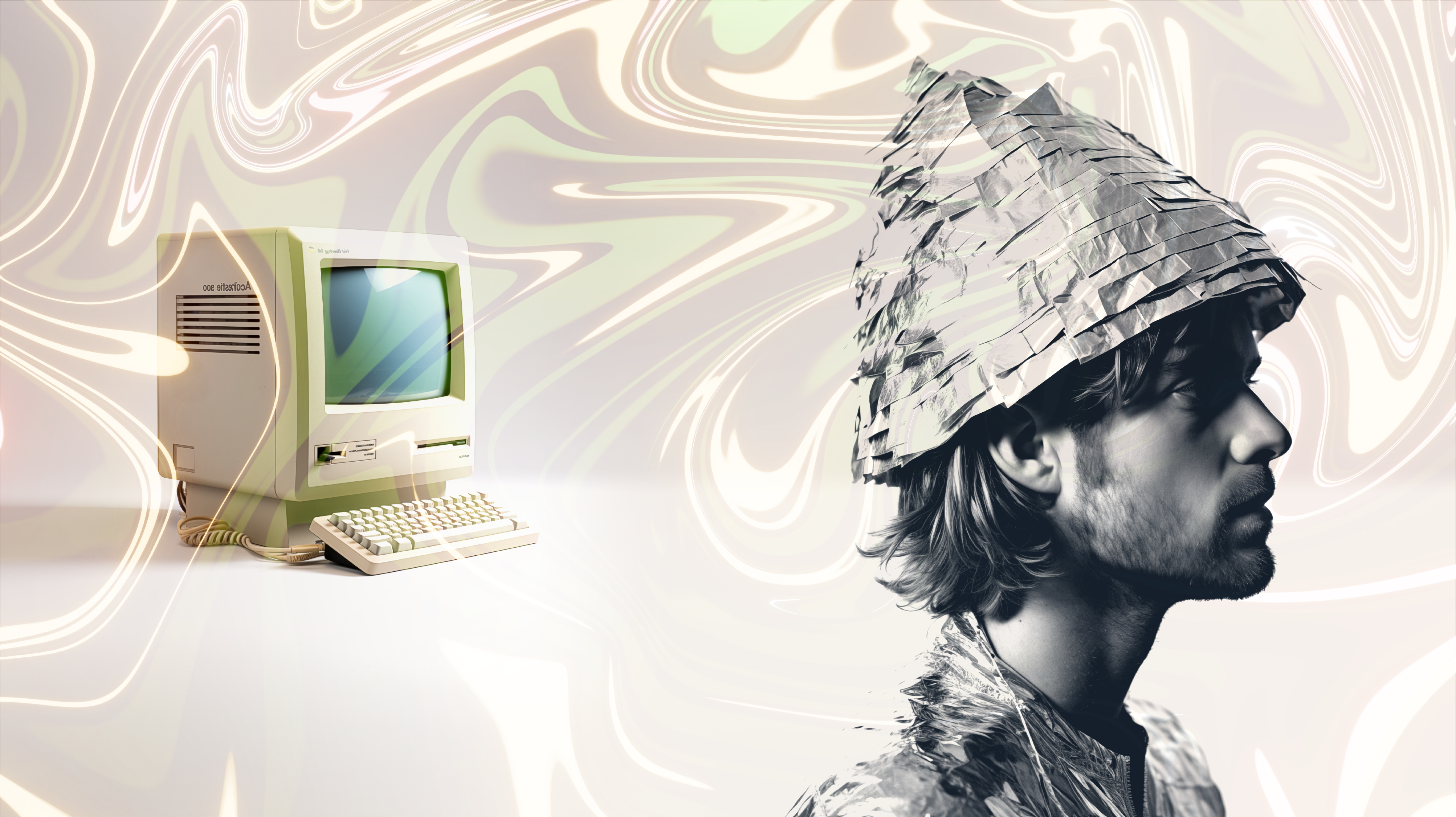

In Postman’s day, this meant that America was developing television brain—a way of thinking about the world mediated by televisual communication. Today, that sounds quaint. We hardly talk about watching television. Instead, we talk about streaming. Our entertainment comes to us largely through AI-generated feeds—Instagram reels, TikTok, YouTube videos—on smartphones, not by human-generated broadcast schedules on cathode ray tube TVs.

We don’t have television brain. We have internet brain. If Postman were alive today, I have no doubt he’d conclude we’d completed our “descent into a vast triviality,” a world where information is contextless, disjointed, and pell-mell—short bursts of uselessness designed for a culture with a deficit of attention, creating a growing inability to think well, reason thoroughly, and sift matters of importance from wasteful distraction.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Because before making such a claim, one must first prove that the mediums of our communication actually shape how we think and what we communicate.

Put differently: Does using the internet cause irreparable brain damage?

Convenient Conversations

Everyone knows how irritating it is when someone sends a message in a text that should have been a phone call. Or calls a meeting when there could have been an email. We intuit that certain mediums naturally mediate certain conversations better than others.

What we rarely consider is that when we read, watch, or listen to online content, the same reality applies. In the words of Marshall McLuhan, the medium is the message. Yes, this old aphorism is old hat, but Postman presses the insight further:

How we are obliged to conduct such conversations will have the strongest possible influence on what ideas we can conveniently express. And what ideas are convenient to express inevitably become the important content of a culture.

It’s not merely that the medium shapes the message. It’s that a culture’s preferred mediums make certain messages possible and impossible. Whatever medium of communication predominates in a culture—be it words or pictures or videos or social media feeds—has a way of downvoting information it can’t accommodate and upvoting information it makes convenient.

If you’re describing a scandal in an institution, for example, a long-form medium such as a report based on interviews and findings offers space for nuance, careful insights, and thoughtful recommendations about how victims might be helped and future scandals might be prevented.

But when you transpose that scandal into a 60-second TikTok video, a thread on X, a headline, an article, or a podcast (inevitably a dialogue between people distant from the situation, who consumed all the aforementioned items), the description of the scandal changes. Not merely because of its length, but because of its goals: most of these mediums are designed to entertain and seize bursts of audience attention.

Moreover, they often include images embedded into links and feeds that make other forms of communication convenient. One recent example: after Matt Chandler voluntarily stepped aside from ministry after sharing careless and unwise DMs with a woman on Instagram, Christianity Today posted an article with the ominous headline, “Matt Chandler Steps Aside After Inappropriate Online Relationship.” This was the image they posted with the article:

Image Credit: Christianity Today, YouTube screen grab.

He’s making an almost childish “oopsie” face. It would be comical if the entire situation wasn’t so fraught, not just for Chandler, but for the woman he was DMing, and the Village Church itself. With sparse details—he’s since been restored to ministry after an investigation, which led to a nuanced long-form report—they communicated via headline and image that Chandler may have done something nefarious and thought it was an “oopsie” situation.

The fact that this was the second-most-read article of 2022 underlines that it was inevitably shared on social media feeds where, at the time, people would only see the image and headline and then have the opportunity to respond with their own reactive, short-form takes as amateur experts on a situation they knew little about.

You see, the medium is the message, and the medium makes certain messages convenient, and whatever messages are the most convenient and pervasive shape a culture’s discourse, and thereby shape how we think—not just about a single message, but about everything.

That is internet brain: at once reactive and amused, serious and ill-informed, expert and amateur. Internet brain is characterized by shallowness: we know something about everything, and yet know nothing about anything. A mile wide and an inch deep, as they say. But of equal importance is the internet brain’s fixation on entertainment: what we give our shallow attention to is what amuses us, evokes wrath, stimulates lust, and stirs frivolity. It is the scrolling brain—the one that phase-shifts through contextless, disjointed information with ease but finds itself seized by paralysis when it attempts to slow down, dig deep, and think long thoughts.

Speaking personally, I can recognize that my own thinking and reading habits are not what they were ten years ago. And all of this has me thinking: What if we all need to incorporate practices, rooted in the second commandment, that counteract internet brain?

From Graven Images to Words

While Postman credits McLuhan with popularizing the connection between medium and message in the modern era, he suggests the idea has a much more ancient pedigree. On a desert mountain in the Sinai peninsula, Moses inscribed a law from God that transformed a community’s worship from image-based to word-based:

“You shall have no other gods before me. You shall not make for yourself an image in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below.” (Exodus 20:3-4)

This single command shifted the locus of Israel’s worshiping life from image to word. They would become a people of the text, who encountered God through its public reading. The words, yet to be written, of the prophets, kings, and wisemen would shape the minds, hearts, and habits of Jews, and later Christians—not just in our conception of the common good or in the formation of character, but in how we interacted with the world of ideas of information around us.

While the command against images strikes us as prosaic, even banal, it would have shocked ancient people. Why not make images?

Postman writes,

It is a strange injunction to include as part of an ethical system unless its author assumed a connection between forms of human communication and the quality of a culture. We may hazard a guess that a people who are being asked to embrace an abstract, universal deity would be rendered unfit to do so by the habit of drawing pictures or making statues or depicting their ideas in any concrete, iconographic forms. The God of the Jews was to exist in the Word and through the Word, an unprecedented conception requiring the highest order of abstract thinking. Iconography thus became blasphemy so that a new kind of God could enter a culture. People like ourselves who are in the process of converting their culture from word-centered to image-centered might profit by reflecting on this Mosaic injunction.

It is striking that Jesus, whom Paul calls “the image of God” on multiple occasions, is still inextricably connected to the typographic world. John calls him “the word,” and while Jesus never wrote any words (at least words we still have), his followers did so in the tradition of the Hebrew prophets and sages.

One cannot deny that a word-based culture, whether it be through the act of reading or being read to, is inherently part of the kingdom’s structure. Yes, we must be doers of the word, but it is the word that tells us what to do and shapes our life together. For a time, this happened through the word-based culture of orality. After the printing press, it continued through the word-based culture of typography. But now we are moving backward into an image-centered culture of symbology, entertainment, and AI-curated content.

There is a ghost in the audiovisual social media machine, and it’s not holy.

The only resistance I can imagine is precisely the form of resistance the ancient Hebrews deployed. They did not totally remove symbology from their worship. The Tabernacle was a pictographic Garden of Eden, with trees, angels, animals, and even a cosmic sea. I cannot go all the way with Postman: visual modes of expression are a valuable part of our worship and life together.

But what would it look like if Christians recentered themselves on the word? Not just the word of God, but words in general. For me, this looks like a ritual of putting all screens away for a prolonged period while I read.

I simply cannot comprehend a page with a phone in my pocket.

The only way to retain some semblance of a typographic mind is by limiting how much entertainment we consume. How many images we intake. How much disjointed, disconnected, and trivial (at least from the perspective of our localized concerns) information we consume.

Perhaps it’s too late. As the Borg loved to say, “Resistance is futile.” But is it?

Topics: